My first visit to the Prince Charles Cinema was sometime in the summer of 2008. I was staying at a friend’s flat while job hunting and doing interviews for various journalism jobs, unaware of the looming financial crisis that was at that point only five or six weeks away, and had an afternoon to kill. Like anyone who cared about film and had the internet around that time, I had heard about it. Tarantino, near the end of the peak of his influence but still incredibly influential to me personally as a 21-year old white man, had already at that point given the PCC his blessing as a sort of spiritual cousin to 42nd Street Grindhouses, or the drive-ins across LA and the American South, as a home away from home for weird movies and weird people, a place driven by a sense of community and a love for films of all flavours. In a quote used on Prince Charles publicity materials for years, he said that “The day that Kill Bill plays at the Prince Charles will be the day that Kill Bill truly comes home!" And this was enough for me, what with Kill Bill being a big deal back then.

I has earmarked that free afternoon for a few weeks in advance and was delighted to see that the time lined up with a screening of Brazil, a film that at that time in my life I absolutely loved for its invention, jet black humour and its gnarly, borderline confrontational bleakness. I’m not so keen on it now.

I went along and sat in the dark for the matinee showing – nowhere near full, but full enough to make you go ‘Huh!’ on a Wednesday afternoon - watching Terry Gilliam’s tale of a middle aged man having an existential crisis while living in dystopian, hopeless future stripped of art and community and creativity, and, in a cruel foreshadowing of my entire twenties, basically took none of it in. All I could think of was: Wow. It is so cool that this is something that you get to do when you live in London!

I moved to the city a few weeks later to start my new job (just in time for that financial crisis!), becoming one of the many, many people who make up London’s community of working people who have come to the capital from elsewhere, with a bindle full of dreams and ambitions and a pocket full of pre-conceptions about what it’s actually like to live here, while also immediately contributing to a rapidly widening inequality by unwittingly paying exorbitant rents in previously accessible areas, fuelling widespread gentrification and continuing to push out the local Londoners. I was one of thousands of clueless kids, in other words, looking for a steady foothold in the world, largely ignorant to genuine social responsibility, and blithely unaware of the dark forces shaping the future of city around me, and my own complicity in making them worse. I was just looking to get my life underway.

I feel pretty confident if you are in this bracket of people who came to live in London from the late 90s onwards, you learned about and potentially visited the Prince Charles Cinema almost immediately, due to the powerful combination of three crucial elements: 1) the tickets were cheap and you likely had very little disposable money; 2) it’s centrally located among some of the most famous landmarks in the world, making it easy to meet people and orient yourself, no matter what part of London you had to eventually return to; and 3) it’s something that you didn’t have at home: a rep cinema with a community and a personality and a slate of programming that might genuinely end up expanding your horizons, and a passport to accessing a new, hitherto unobtainable cultural world that just wasn’t as accessible in other parts of the UK, certainly at that time (although there has been a noticeable and cheering boost in community led rep cinemas in the last decade or so). As a result, almost everyone who has lived in London and engaged with its cultural scene over the past few decades likely has an affection for, and important memories, of the Prince Charles Cinema – it has to be one of the city’s most cherished and popular date venues, if nothing else. How many people started, forged, ended relationships there? Hundreds? Thousands? 130,000?

That might account for the 130,000 signatures on this petition at the time of writing, protesting Zedwell LSQ Ltd and their parent company Criterion Capital’s attempts to re-negotiate the Prince Charles Cinema’s lease at a punishingly high level, well above market rates, while including a break clause that appears, for all intents and purposes, to be a confirmation of future eviction and development. Not nice, but still: 130,000? Do people still really care about Kill Bill that much?

Of course not - no one cares about Kill Bill any more. What I do think this outpouring is actually representative of is something that I think people frequently underestimate about the Prince Charles – it’s not the Scala, which was a barely legal underground club run by and frequented by legitimate outsiders and misfits that frankly was lucky to avoid being shut down for as long as it did; neither is it the mecca for film nerds that Quentin Tarantino anointed it as, and its reputation as a home for exploitation cinema is not really the case, and hasn’t been for a while. Core elements of its programme are the normie-oriented Sound of Music sing-alongs (only recently stopped after 24 years of consistent showings) and Lord of the Rings all-nighters and servicing the seemingly bottomless desire for more screenings of Interstellar. Even the more cine-literate programming now has evolved in line with the needs of the Letterboxd generation – instead of the blood and guts, hyper-macho Argento and Tarantino and James Cameron dominating the schedule (they’re still there, just less prominent), it’s world cinema titans like Wong Kar-Wai and Edward Yang and Satoshi Kon and Chantal Akerman who seem to be packing them in, encouraging a clientele that’s as friendly to women and LGBTQ+ audiences as it is to the stereotypical film bros.

That’s the remarkable thing about the Prince Charles: it has felt for a very long time like it is truly servicing the whole of London, giving equal weight to all tastes and areas of interest and fandom. In this way, it feels like the rarest thing in our modern city - a truly egalitarian community space.

But crucially, it’s not only that – it’s a successful and profitable independent business, one not in any financial straits (that I know of), or apparently with any pressing need to sell. It is, or should be, the leading example for any supposedly pro-business government, of what a smart business strategy and an engaged community can achieve. The report card for the PCC is A+ across the board – whether that’s public approval, community engagement, public service, or its own self-sufficiency.

But none of that matters, because as we know we live in a world where none of that matters. London is demonstrably a town that is controlled and in the process of having its landscape be redrawn permanently by billionaire slumlords, who either don’t care or don’t understand the needs and desires of London’s actual community. Their only aim is to acquire it all, as quickly and as quietly as possible. It’s nothing personal – just the inexorable march of late capitalism.

But of course, it’s always personal.

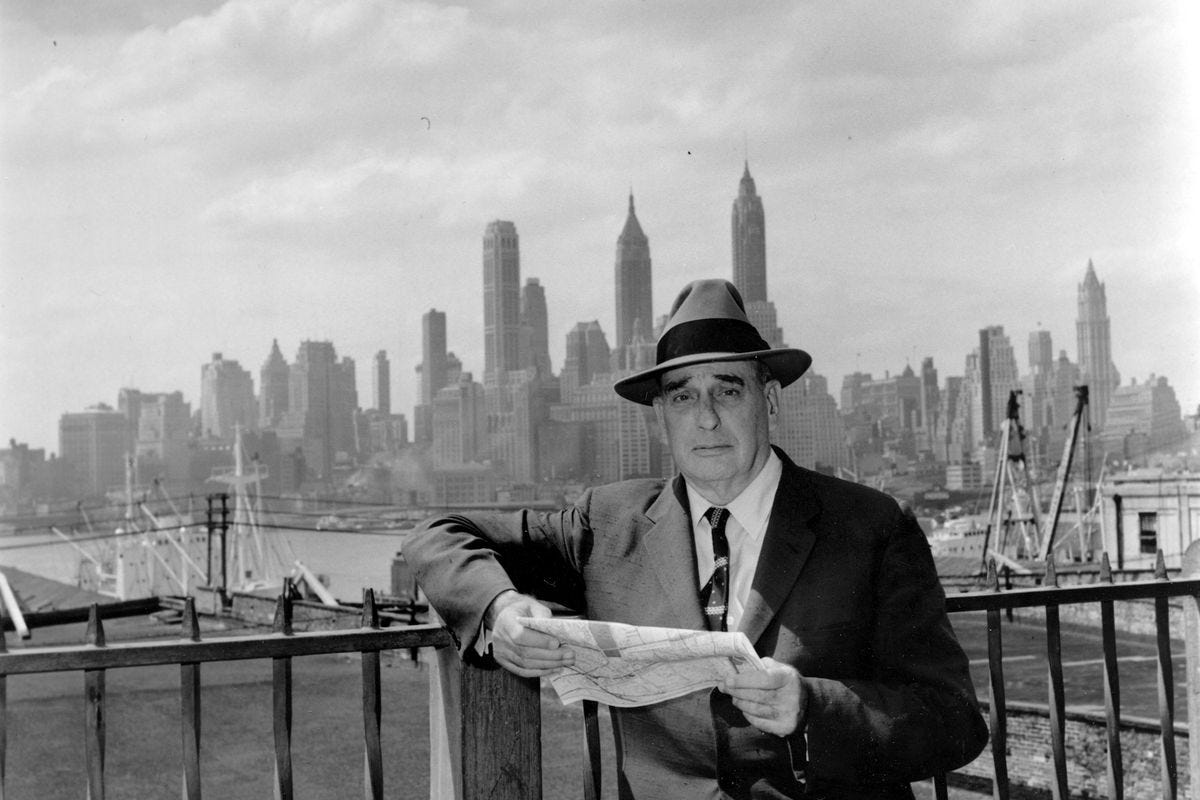

Back in the news this month is Robert Caro’s The Power Broker, after the legendary work of biography was finally released in the UK in mammoth, 66-hour audiobook form. It’s a book that has always been relevant and timely – nevertheless, the timing of this release feels especially pointed.

The subject of the book is Robert Moses, a New York public official and urban planner who shaped perhaps more than anyone the landscape of New York City, approving hundreds of planning projects, including highways, bridges, and parks, many of which were hugely popular with residents but would also result in the displacement of over a dozen neighbourhoods; also, in their hyperfocus on commuting via car, his plans set back the public transit system of the city for decades. A largely unapologetic racist, Moses would also apparently target Black and brown communities vindictively when making decisions, and aside from the tragic and disruptive displacement he oversaw he would often directly intervene in policy to deliberately make their lives harder, in an attempt to keep them away from his developments and make them more ‘attractive’. He built 255 playgrounds in New York City in the 1930s – only two of these were in black neighbourhoods, despite frequent begging letters from Black citizens for somewhere for their children to play that wasn’t in the crumbling and dangerous streets. In the most infamous example of his racist cruelty, he instructed the managers of the one swimming pool that neighboured a black community to lower the temperature of the pool by several degrees, based on his belief that ‘[Negroes] don’t like cold water’.

His personal biases - it’s always personal - were imposed on the city of New York at a drastic scale, causing decades of harm and neglect - and yet Moses was never democratically elected to a position of government in his life. Through a combination of some good fortune and extreme political skill (although admittedly this skill mainly boiled down to threatening to resign over and over again), he was able to navigate himself into a position where he was able to effectively redraw the city of New York in his own image, with a succession of supposedly powerful gubernatorial figures apparently having no choice but to get out of his way, lest their own tenuous grip on power be threatened. This was the reason Caro was moved to write the book - how can an unelected official achieve a position where they are allowed to shape the lives and destinies of millions?

I thought about Robert Moses and The Power Broker recently when I saw that grim selfie of Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, and Jeff Bezos at Trump’s inauguration – a depressing reminder that all the people with actual power in our modern world are unelected, much like Moses was. The big difference compared to the Moses era, however, is how capital is now directly equivocal to power, as trite as it sounds to say. Moses was never a rich man, and never courted money particularly – he cared about having the power to create his vision of New York City. Now, there’s no such thing as soft power, really – the richest men in the world are the most powerful men in the world, and that’s our reality. We’re in the billionaire autocrat era.

So Robert Moses and The Power Broker were already on mind when I angrily started looking up Zedwell LDQ and Criterion Capital, after the news broke about the Prince Charles. The CEO of these companies – and, it turns out, a man linked to many other companies that own a huge proportion of Central London - is the same man: Asif Aziz.

A small amount of research and something is immediately clear – this is a billionaire with unimaginable wealth and probably the most significant property portfolio in London. Like Moses, in his acquisition and development strategy he is by his own admission and ambition making decisions that are shaping the centre of the city forever, despite not being elected, answerable to London’s citizens, or even particularly publicly visible. Criterion Capital absolutely does not need to add the Prince Charles Cinema to that portfolio, nor does it need the huge hike in rent that is negligible in the context of his personal fortune, but existential for the cinema. So why? Why are they doing this? Why is he doing this?

Like Moses, Aziz is notoriously publicity shy. His only interviews available online are with fawning corporate periodicals who describe him as as outsider figure and a self-made success– a self-made success who was educated at the £52K a year Wandsworth School, and began his empire by acquiring two shops and converting into flats in Deptford at the age of sixteen – and level him the softest of softball questions, something something your campaign to own all of London appears to have the momentum of a runaway freight train, something something why are you so popular?

There’s absolutely no evidence he has a vindictive or racist agenda like Moses; then again, there’s no evidence that he stands for anything at all, besides his philanthropic organization, which remains entirely distinct from the way he actually makes money and is therefore not relevant to any of this, any more than the Sackler Trust is relevant to their role in the opioid crisis. In interviews there’s some half-hearted nods from him about his dream of London being a city of windowless hotels as somehow related to climate change, but from what I’ve read it doesn’t seem like his heart is much in that as a philosophy. Any mild attempts by interviewers to broach people’s displeasure with how he operates is dismissed with a robotic lack of engagement: “I have never been worried about people’s perceptions… you can never make everyone happy… The greatest lesson I've learned is that I will continue to make mistakes until the day I die, and I continue to persevere”, before adding that he is own ‘biggest personal critic”. Well, don’t speak too soon, you fucking dickhead.

Going after the Prince Charles appears on the surface to be purely motivated only by a staggering, all pervasive greed, wilfully ignoring what is the clear will of the London community that Aziz has frequently argued he is engaged with and acting in the best interests of. To make this move feels deeply personal. Why should the wishes of over 130,000 not outweigh the wishes of one man’s desire for more money, more real estate? And why is it all happening out of sight? Why don’t I know who he is, what his motivations are? I’m writing this in a week where – against my will – I have learned the sexuality of a Premier League referee, because a paper deemed it enough in the public interest to make it front page news. And yet I know almost nothing about a man who owns London’s West End, besides the following previously reported facts:

As of 2023, Aziz has a £3.8bn net worth, with a £3.6bn property portfolio, with a large concentration of these properties being in the heart of the West End of London. According to an interview with Professional Wealth Management, his focus is buying and developing “end of life buildings and derelict spaces” (it would be interesting to hear how this emphasis squares with the plans for The Prince Charles Cinema, which has never been more popular and less derelict) before turning them into hotels or ‘affordable’ flats. Last month Criterion Capital acquired and gave notice to shut down the oldest YMCA in the world - initially it issued a statement that it planned to meet with local organisations and stakeholders in the YMCA to discuss future plans for the building, but is now refusing to pick up the phone to anyone. In recent years, Criterion Capital/Zedwell also acquired the Trocadero (another site that blew my mind when visiting London as a child, a ludicrously ambitious theme park-cum-entertainment centre) and redeveloped it into 712-room windowless hotel, with prices starting at £142 a night.

Private Eye and the journalist John Lubbock have reported over the years on companies that are either directly owned by and linked to Aziz that have acquired and shut down dozens of pubs and community spaces for redevelopment of luxury flats. The Times – hardly a publication that is known for being typically hardline in its assessment of landlords or venture capitalists – called Asif ‘the meanest landlord in Britain’ due to his treatment of tenants during the pandemic. Asif has has insisted in interviews that he doesn’t own any pubs and has never evicted any private tenants, presumably on the basis that technically the landlord name is the company he owns and not him personally. (Of course - it’s never personal.) The only piece of early biography we know is the aforementioned story of him buying two shops at the age of sixteen, before moving to Angola to ‘make his fortune through the setting up of food manufacturing and distribution businesses’. Private Eye reported that he later sold an Angolan food manufacturer to the the Lebanese Tajideen family, adding that “the deal turned sour, however, and in 2010 the new owners sued Aziz in the high court over claims that Aziz had exaggerated the value of the companies and falsified a series of expense claims. In one email Aziz asked his chief accountant: ‘Will they check each figure – can we not bullshit the numbers another way? Food for thought.’” That’s about everything on public record, apart from one more tidbit from Aziz’s divorce hearing – in order to avoid a divorce settlement where he would have to split his fortune with his wife, he argued that he and his wife were never actually married, but instead obtained a fake marriage certificate in order to obtain a passport for their adopted son.

I only know all this because I have spent the last few days looking up everything I can about this man and his companies. I’ve done this because I suddenly feel as if it’s my duty to know; that knowing who is responsible for this is the most urgent thing in the world.

Having to think about the Prince Charles potentially closing means thinking about those early years in London, where I was penniless and excited and hanging out with my friends at the cinema and wondering what life had in store for me. It means thinking about the four times I got made redundant, about the financial crash, about having to change careers several times as I couldn’t afford to make rent, about several occasions where I avoided having to move back home and in with my parents by the skin of my teeth, about the endless redevelopment and gentrification and spiralling rents in the nine or ten different neighbourhoods I moved to within eight years, about the closure of clubs and dying nightlife and the idea of anything ever being open past 1am petering away. I think about my friends who I made in that period now, moving further and further away from the city or out of it entirely, so we can start families and afford to live in non-shared flats, or perhaps even own a home if you are someone lucky enough to have a family member who will be able to fund the deposit. I think about how our salaries have barely moved in over a decade, and I think about the super rich, and I think about billionaires, and how my entire existence in London has been dictated by these people, and I think about how it will never, ever stop, as nothing will ever be enough for them.

Of course it seems desperately unfair and cruel that these companies and the men who run it, who already effectively owns 95% of the West End, should also want to brutally snatch away the 5% that everyone likes, the part that’s actually accessible to Londoners. But to quote Adam Serwer on another powerful real estate magnate, the cruelty is the point. Criterion Capital and all the other offshore developers have demonstrated in their behaviours again and again that community value and cultural significance are just barriers to their goals, and not ones they will ever seriously. And that goal is ultimately the same as any other billion dollar company, or billionaire, who are just adhering to the terminal logic of late-stage capitalism: it’s not just that they want to own everything: they want us to own nothing.

Look: I get it. It’s just a cinema. Cinemas shut down, or move. It happens. The rents must go up. The forces of capitalism must march on unhindered. But if the Prince Charles, a beloved, financially solvent cultural institution that has played by the rules and succeeded on its own merits, can be potentially strongarmed out of the building by billionaire developers while supposedly progressive politicians like Sadiq Khan and Rachael Blake and Keir Starmer and London ‘night czar’ Amy Lamé (the accent on that e really doing an extraordinary amount of heavy lifting) put their hands in their pockets, whistle and look the other way, then truly the city will be forever lost to the slumlords and their sterile, narrow dreams, and me and my generation of people who came to London to build lives (never mind the native Londoners, long abandoned or banished) will relocate back home somewhere more affordable along the M25 to remote work until we are dead or 75, leaving behind the windowless hotels and derelict flats and pointlessly oscillating elevators to nowhere to sit unloved, unoccupied and silent, only occasionally interrupted by the odd echoing squeak from a baffled mouse who now is the sole occupant of a giant windowless tower block that once used to be a cinema; a place where 347 people once met their future spouses, where dozens people got to watch the 1990 Brian Bosworth film Stone Cold for the first time, where a lunatic of indeterminate European origin would inexplicably come and read sonnets and do push-ups every few months in front of an adoring sold-out crowd, and where several gallons of tears were shed – happy, sad, confused - as people took time out of their fast-paced, stressful lives in a brutally unforgiving city to sit quietly for a few hours and be transported and moved by the images they saw up on the screen.

It’s depressing. I do believe the Prince Charles Cinema will survive. But saving it won’t be easy. And what I won’t do – what I can’t do – is once more idly let my turbulent life in this city continue be changed for the worse by faceless forces that I don’t know and that I don’t understand. Asif Aziz, Criterion Capital/Zedwell directors Faizan Ahmad and Danish Hanif, and all the other offshore developers carving up London: I want people to know your names and I want everyone to know what you’re doing. I want you to look us in the eye while you take our city away from us. You have made this personal.

But then again, it’s always personal.

Movies aren’t dead - please sign the petition to save the Prince Charles Cinema here.